Tsunami Protection Methods

Written

and prepared by Dan Rokser

for Professor

Chin Wu, Ph.D.

University

of Wisconsin-Madison

Department

of Civil and Environmental Engineering

CEE 514:

Coastal Engineering

Spring

2003

Tsunami Protection Methods

Written

and prepared by Dan Rokser

for Professor

Chin Wu, Ph.D.

University

of Wisconsin-Madison

Department

of Civil and Environmental Engineering

CEE 514:

Coastal Engineering

Spring

2003

Introduction

Tsunamis are infrequent but very dangerous natural

hazards that threaten the coasts and inland waters of California, Oregon,

Washington, Alaska, Hawaii, and territories in the Pacific region, as well

as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands in the Caribbean. The Cascadia Subduction

Zone (CSZ) just offshore in the Pacific Northwest and the Aleutian Seismic

Zone are of particular concern, given the potential there for very large,

destructive events. U.S. seismologists put the probability of a major Alaskan

earthquake of magnitude 7.4 or greater in the next decade at 84 percent.

Along the CSZ, the probability of a magnitude 8-9 event is 10 to 20 percent

in the next 50 years. Tsunamis generated by such events will reach coastlines

in as few as 15 minutes. A 7.4 to 8 sized earthquake could generate a tsunami

with heights up to thirty feet in the air. A 8 to 9 event could produce

a tsunami with a wave height up to one hundred feet in the air spelling

catastrophic consequences for the entire Pacific coast line.

What is a Tsunami?

What are the Protection Methods Against Tsunamis?

The National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program

Are there Tsunamis that we can't protect against?

References

A tsunami (pronounced tsoo-nah-mee) is a

wave train, or series of waves, generated in a body of water by an impulsive

disturbance that vertically displaces the water column. Earthquakes, landslides,

volcanic eruptions, explosions, and even the impact of cosmic bodies, such

as meteorites, can generate tsunamis. Tsunamis can savagely attack coastlines,

causing devastating property damage and loss of life.

Tsunami is a Japanese word with the English translation, "harbor wave." Represented by two characters, the top character, "tsu," means harbor, while the bottom character, "nami," means "wave." In the past, tsunamis were sometimes referred to as "tidal waves" by the general public, and as "seismic sea waves" by the scientific community. The term "tidal wave" is a misnomer; although a tsunami's impact upon a coastline is dependent upon the tidal level at the time a tsunami strikes, tsunamis are unrelated to the tides. Tides result from the imbalanced, extraterrestrial, gravitational influences of the moon, sun, and planets. The term "seismic sea wave" is also misleading. "Seismic" implies an earthquake-related generation mechanism, but a tsunami can also be caused by a nonseismic event, such as a landslide or meteorite impact.

Tsunamis are unlike wind-generated waves, which many of us may have observed on a local lake or at a coastal beach, in that they are characterized as shallow-water waves, with long periods and wave lengths. The wind-generated swell one sees at a California beach, for example, spawned by a storm out in the Pacific and rhythmically rolling in, one wave after another, might have a period of about 10 seconds and a wave length of 300 ft. A tsunami, on the other hand, can have a wavelength in excess of 65 miles and period on the order of one half to a full hour.

As a result of their long wave lengths, tsunamis behave as shallow-water

waves. A wave becomes a shallow-water wave when the ratio between the water

depth and its wave length gets very small. Shallow-water waves move at

a speed that is equal to the square root of the product of the acceleration

of gravity (32.2 ft/s^2) and the water depth - let's see what this implies:

In the Pacific Ocean, where the typical water depth is about 2.5 m, a tsunami

travels at about 450 mph (the speed of a fighter jet!). Because the

rate at which a wave loses its energy is inversely related to its wave

length, tsunamis not only propagate at high speeds, they can also travel

great, transoceanic distances with limited energy losses. As they

approach land, tsunamis slow down again related to C=Squrt. (GD), and the

water column rises with the ocean bed creating huge walls of water.

Although, approaching water is slowed by the depth, water behind will continue

to push the water column forward developing a wave that will move over

land without losing energy to breaking enabling it to move large distances.

This

animation

(2.3 MB), produced by Professor Nobuo Shuto of the Disaster Control Research

Center, Tohoku University, Japan, shows the propagation of the earthquake-generated

1960 Chilean tsunami

across the Pacific. Note the vastness of the area across which the tsunami

travels - Japan, which is over 17,000 km away from the tsunami's source

off the coast of Chile, lost 200 lives to this tsunami. Also note how the

wave crests bend as the tsunami travels - this is called refraction. Wave

refraction is caused by segments of the wave moving at different speeds

as the water depth along the crest varies. Please note that the vertical

scale has been exaggerated in this animation - tsunamis are only about

a meter high at the most in the open ocean.

Due to the size and speed, there is no way to stop a tsunamis after it has been set in motion. The Japanese government has invested billions in coastal defenses against tsunamis -- for example, building concrete sea walls to blunt the impact of the waves and gates that slam shut to protect harbors. One such wall, standing about 15 meters high and made of reinforced concrete, was built on Japan's Okushiri Island after it was struck by a tsunami that killed 120 people in 1993. Although breakwaters do reduce the waves, most experts agree that breakwaters or seawalls could not be built high enough or strong enough to hold the water back completely. So for large tsunamis, the rule is this: You can run, but you can't hide. So tsunami hazard experts are working on ways to make sure people know when a tsunami is coming and where they can run to get out of harm's way. The following are the two tsunami warning systems in use today for protection against tsunamis:

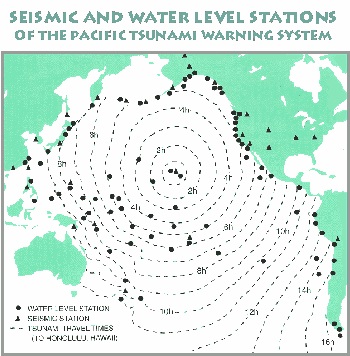

The Pacific Tsunami Warning System

The Pacific Tsunami Warning System consists of a series of seismic monitoring stations and a network of gauges (See Picture) that measure sea levels. When a seismic disturbance is detected, its location and magnitude are computed. In some susceptible regions, warnings are issued if the magnitude is above a certain threshold. Then the gauging stations are monitored for abnormal changes in sea level. If a tsunami is detected, computer-based mathematical models are used to calculate its speed and direction – taking into account diffraction, refraction and reflection effects, as well as peculiarities in the shape of the sea bed. Coastlines lying in the predicted path of the tsunami are warned of the approaching wave train. The real problem with this system is that since its inception, 75 % of the warnings issued through this system causing millions of dollars of unnecessary evacuation costs.

`

DART Warning System

The new system in development is the Deep-ocean Assessment and

Reporting of Tsunamis system (DART). Each DART station is comprised of

two main components: a Bottom Pressure Recorder (BPR) and a Surface Buoy.

The figure to the right shows a sketch of the DART System.  The BPR is the heart of the system and resides on the sea floor during

its deployment. It consists of a pressure gauge programmed with a sampling

scheme that yields a full ocean depth resolution of approximately 0.25

millimeters (mm) of water. The BPR also contains one-half of an acoustic

link and associated electronics and battery packs to power the system for

two years without being serviced. The entire BPR is attached to an anchor

via an acoustic release. Every two years the BPR is serviced by triggering

the acoustic release and recovering the BPR platform after a series of

glass ball flotation has raised it to the surface of the ocean. The surface

buoy is used to transfer information from the BPR to the Tsunami Warning

Centers via a Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES)

transmitter. The buoy is moored in approximately 3000 to 5000 meters (m)

of water (depending upon the station) via a taut nylon mooring. It is equipped

with the other half of the acoustic link for sub-surface communications

with the BPR and has batteries sufficient to allow for a one year deployment.

Basic DART operations begin with the BPR measuring water surface levels

and transmitting data across the acoustic link to the surface buoy hourly.

The data received by the surface buoy is re-transmitted via the GOES. The

presence of a tsunami is detected by measuring a mean change in the water

level of greater than 3 centimeters (cm). Then, a tsunami mode is triggered,

causing the BPR to continually update the surface buoy with water level

averages, and the data are transmitted in real-time via the GOES. All of

these data are transmitted to the Tsunami Warning Centers. With the data

from these systems, along with information from other measurement systems

(e.g., seismic measurements, tide gauges) and numerical models, the

warning centers can then determine if tsunami warnings should be issued

to the appropriate coastal communities.

The BPR is the heart of the system and resides on the sea floor during

its deployment. It consists of a pressure gauge programmed with a sampling

scheme that yields a full ocean depth resolution of approximately 0.25

millimeters (mm) of water. The BPR also contains one-half of an acoustic

link and associated electronics and battery packs to power the system for

two years without being serviced. The entire BPR is attached to an anchor

via an acoustic release. Every two years the BPR is serviced by triggering

the acoustic release and recovering the BPR platform after a series of

glass ball flotation has raised it to the surface of the ocean. The surface

buoy is used to transfer information from the BPR to the Tsunami Warning

Centers via a Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES)

transmitter. The buoy is moored in approximately 3000 to 5000 meters (m)

of water (depending upon the station) via a taut nylon mooring. It is equipped

with the other half of the acoustic link for sub-surface communications

with the BPR and has batteries sufficient to allow for a one year deployment.

Basic DART operations begin with the BPR measuring water surface levels

and transmitting data across the acoustic link to the surface buoy hourly.

The data received by the surface buoy is re-transmitted via the GOES. The

presence of a tsunami is detected by measuring a mean change in the water

level of greater than 3 centimeters (cm). Then, a tsunami mode is triggered,

causing the BPR to continually update the surface buoy with water level

averages, and the data are transmitted in real-time via the GOES. All of

these data are transmitted to the Tsunami Warning Centers. With the data

from these systems, along with information from other measurement systems

(e.g., seismic measurements, tide gauges) and numerical models, the

warning centers can then determine if tsunami warnings should be issued

to the appropriate coastal communities.

Recently the DART system hit the bull’s-eye Nov. 17, 2003 when it detected

a small tsunami generated by an earthquake near Adak, Alaska. “This

was the first time since it went operational in October that we had a chance

to put it through its paces and it worked as planned,” said Eddie N. Bernard,

director of the NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle,

Wash., where the warning system was developed, designed and built. “This

is the first time we were able to capture tsunami data in real-time in

an operational mode.” While the buoys worked well during the research

phase, Mother Nature on Nov. 17 offered up a 7.5 earthquake in the Aleutian

Islands, the first such test of the system in operational mode. This earthquake

was similar in magnitude to an event from the same region in 1986, which

triggered a tsunami warning that resulted in the evacuation of Hawaii coastal

areas. The tsunami that ultimately struck the Hawaii coastline, however,

was less than a foot in height and caused no damage. The average cost of

lost business and productivity because of the evacuation was estimated

by the State of Hawaii’s Department of Business, Economic Development and

Tourism to be $40 million. The State of Hawaii’s response to this most

recent earthquake/tsunami cost about $68 million less (adjusted for inflation)

because, for the first time, real-time data were available, and no evacuation

was ordered.

Protection methods have developed over the years and they have been encompassed into what is called the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program. This program was established in 1992 and is designed to reduce the impact of tsunamis through:

Warning Guidance

The program will use the information gathered from the Pacific Tsunami Warning System and the Dart System to issue accurate warnings and watches for the affected coasts. This program also uses recently developed modeling systems to accurately predict the run-up and the flooding zones of the on coming wave.

Mitigation

The program also informs affected coasts on the possibility of tsunamis using brochures, warning signs, lectures, and information lines. The public is informed what to do before, during, and after a tsunamis occurrence. Through knowledge and preparedness, lives can be saved from this natural disaster.

Hazard Assessment

The program finally identifies "high-risk"

areas of coast due to diffraction, refraction, and ocean bottom contours.

Then they provide models and maps for possible flooding areas in order

to evaluate possible evacuation routes. They will also look at sensitive

structures such as schools and power plants and give detailed evacuation

plans.

Scattered across the world’s oceans are a handful of rare geological time-bombs. Once unleashed they create an extraordinary phenomenon, a gigantic tidal wave, far bigger than any normal tsunami, able to cross oceans and ravage countries on the other side of the world. Only recently have scientists realized the next episode is likely to begin at the Canary Islands, off North Africa, where a wall of water will one day be created which will race across the entire Atlantic ocean at the speed of a jet airliner to devastate the east coast of the United States. America will have been struck by a mega-tsunami.

These mega-tsunami's are caused by large amounts of earth falling into the ocean. Scientists now realize that the greatest danger comes from large volcanic islands, which are particularly prone to these massive landslides. Geologists began to look for evidence of past landslides on the sea bed, and what they saw astonished them. The sea floor around Hawaii, for instance, was covered with the remains of millions of years’ worth of ancient landslides, colossal in size.

But huge landslides and the mega-tsunami that they cause are extremely rare - the last one happened 4,000 years ago on the island of Réunion. The growing concern is that the ideal conditions for just such a landslide - and consequent mega-tsunami - now exist on the island of La Palma in the Canaries. In 1949 the southern volcano on the island erupted. During the eruption an enormous crack appeared across one side of the volcano, as the western half slipped a few meters towards the Atlantic before stopping in its tracks. Although the volcano presents no danger while it is quiescent, scientists believe the western flank will give way completely during some future eruption on the summit of the volcano. In other words, any time in the next few thousand years a huge section of southern La Palma, weighing 500 thousand million tons, will fall into the Atlantic ocean.

What will happen when the volcano on La Palma collapses? Scientists predict that it will generate a wave that will be almost inconceivably destructive, far bigger than anything ever witnessed in modern times. It will surge across the entire Atlantic in a matter of hours, engulfing the whole US east coast, sweeping away everything in its path up to 20km inland. Boston would be hit first, followed by New York, then all the way down the coast to Miami and the Caribbean.

International Tsunami Information Center-http://www.prh.noaa.gov/itic/library/about_tsu/faqs.html#1

Tsunamis Homepage-http://www.noaa.gov/tsunamis.html

"NOAA’s DART RIGHT ON TSUNAMI TARGET"-http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2003/s2136.htm

"DART Mooring System"-http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/tsunami/Dart/dart_ms1.html

Tsunami!-www.geophys.washington.edu/tsunami/welcome.html

Tsunami Homepage-www.promotega.org/ksu00010/Tsunamis.htm

"Mega-Tsunami"- Wave of Destruction, www.bbc.co.uk/science/horizon/2000/mega_tsunami.shtml

Forces of Nature: Tsunami-http://library.thinkquest.org/C003603/english/tsunamis/whatsatsunami.shtml?tqskip1=1

Wave Picture-http://mega-tsunami.com/